In June 2018, I had the opportunity to study the Advanced Course on Microbiota and the Brain with the Neuroscience Society of Advanced Studies (NSAS) in San Servolo island in Venice, Italy.

Following the overviews in the previous articles, I wanted to share in more detail some of the key learnings, research and takeaways from each week of the course.

WEEK ONE DETAILED INSIGHTS – MICROBIOTA AND THE BRAIN

This week consisted of exploring the research into the gut-brain axis, often called the microbiota-gut-brain axis.

One thing you will not hear the researchers call the gut is ‘second brain’ or ‘third brain’. The gut is not a second brain. It is a gut. It is a very special gut!

When we think of the ‘gut’ we think of the stomach, yet when the researchers discuss the gut-brain axis, they actually include the intestinal tract i.e. mouth and nose as well as the internal organs we perhaps associate with the gut, such as the colon, liver, pancreas, gall bladder, etc.

Most of the current research is focusing on the intestines and colon, although due to ease of access, research tends to analyse what comes out the other end, which may be different to what is going on inside due to bacteria.

What is Microbiota?

The Oxford English Dictionary states that it is “…the microorganisms of a particular site, habitat, or geological period”, although I prefer Wikipedia’s description of microbiota as an “ecological community of commensal, symbiotic and pathogenic microorganisms found in and on all multicellular organisms.”

Basically, your microbiota are all the little bacteria, fungi, viruses and organisms that are a part of you; your ecological community. Without them, you wouldn’t function.

In the past it was commonplace to try and kill these bugs – we invented drugs and antibacterial wipes for every surface imaginable, in order to remove them from our lives.

Until the Human Genome project revealed that we only have around 24,000 human genes and that the rest of us is made up of all sorts of good stuff that work together with our genes to help us process energy and make proteins (among other complex processes). So, now we have realised that a huge part of our make-up is our microbiota and that we need to learn to nurture it.

Let’s start with the basic research findings, bearing in mind it is a new field and there are lots of unanswered questions.

Where do Microbiota come from?

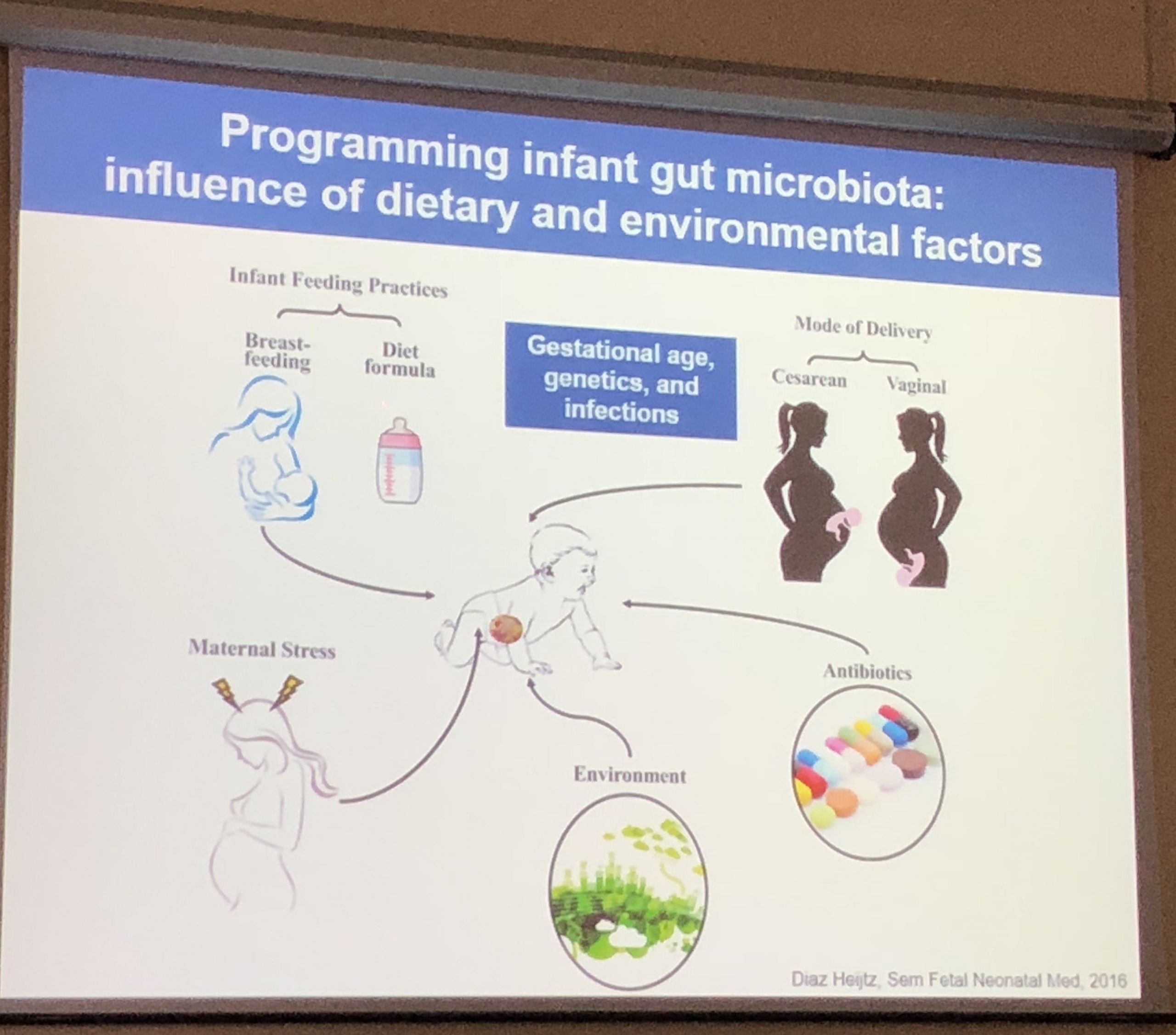

We get our microbiota initially from our mother. When a woman is pregnant, her stress levels, diet and any drugs she is taking all impact her microbiota, and that microbiota is transferred to the child in a number of ways. I won’t go into all of the processes here, yet there are a few key things that are becoming clear from the research.

In a natural birth, the baby comes through the birth canal, past the vagina and anus, and it picks up the beginnings of the bacteria it is going to need. Breast milk also provides the natural bacteria required for the baby as it grows. The levels of bacteria actually change in the milk as the baby develops, as it requires different strains at different points in its growth.

In a natural birth, the baby comes through the birth canal, past the vagina and anus, and it picks up the beginnings of the bacteria it is going to need. Breast milk also provides the natural bacteria required for the baby as it grows. The levels of bacteria actually change in the milk as the baby develops, as it requires different strains at different points in its growth.

For example, it has been found that a kangaroo who has one joey in the pouch, and then produces another, will have two nipples producing milk, with one nipple dedicated to each individual joey. Therefore, nipple A for the older joey will be producing milk that differs in its bacterial strains and levels to the milk from nipple B (for the younger joey).

Yet what if you can’t have a natural birth due to complications? Some doctors are now doing vaginal swabs, so the baby still gets ‘infected’ with the mother’s microbiota – the results of research in this area are mixed, yet the practice is becoming more popular. And what if you can’t breast feed? Again, thankfully the producers of formula are now learning this and formulas are changing.

Changes in our Microbiota

There are other things that can impact or kill microbiota, and antibiotics are a big one. They do not discriminate which bugs they kill, so whilst the increase in antibiotics use has had positive results in some situations, it can be devastating for our microbiota.

Diet is another big influencer of our microbiota. Even if we are not taking antibiotics directly, we are often getting them through foods that have had antibiotics added to them. Antibiotics were used in agriculture before they were used on humans! Infections and the environment are also contributors to changes in our microbiota.

What does this mean for our health?

The impacts of changes in our microbiota are being felt around the world, in what we call NCDs, or non-communicable diseases. These are things like depression, anxiety, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, autism, Fragile X syndrome, multiple sclerosis, chronic fatigue, strokes, obesity and autoimmune disorders.

So many diseases are now found to have connection to dysbiosis i.e. negative changes in the microbiota.

This is really important research and could change the nature of treatment for some of these diseases, or at least provide another perspective. One thing that is more common due to research results to date is FMT i.e a faecal microbiome transplant. Initially, this was not a pleasant experience, as trying to get someone to eat another person’s excrement was not overly enticing. There have been different methods experimented with, and more appealing options are becoming available.

Specially raised germ-free mice are used in the research to further understand this area. A germ-free mouse with no bacteria on it or inside it has lots of issues. Yet research has shown that popping him in a cage with ‘normal’ mice restores his microbiota, as mice eat each other’s poop!

How else can you nurture your Microbiome?

It is the same advice you would have heard many times before – watch your diet. It is not that you are what you eat, it is that your bacteria are what you eat and they help keep you healthy, or not!

This means lots of variety, lots of colour, lots of veggies, less meat, less alcohol and less processed food; all the messages we are already receiving through the media and health care systems.

Yet just because you know this stuff, doesn’t mean you do it. We have a phrase at the Langley Group that we use regularly – “you know it, do you do it?”

Probiotics and Prebiotics

If you are familiar with this topic you will have already learnt about probiotics and maybe prebiotics.

A prebiotic is a non-digestible food ingredient that helps your microbiota – you can’t digest it, yet your bacteria can. Some of these prebiotics can be found in foods such as leeks, onions, garlic, asparagus, artichokes and bananas. It might be time to add more of these to your diet!

There are probiotics that we are more familiar with and it has led to a huge increase in people downing little pots of probiotic yoghurts.

Please note that many of these probiotics do not make a difference as many of the bacteria cannot survive once removed from certain temperatures, or they die on the way down your intestinal tract, so they make no difference once they get to your stomach.

Some great probiotic food alternatives would be kefir, kombucha, sauerkraut, raw cheese, apple cider vinegar, olives and tempeh.

Key takeaways

- Thank your Mum for having you – particularly if she had you naturally and breastfed you.

- Start to love and nurture your bacteria – on your skin and inside it

- Improve your diet – Just take one little step, if not for you, then for your microbiome.

Don’t miss the previous post in this series:

To learn more join Learn with Sue for eBooks on topics such as 7 Ways to Apply Positive Psychology, 10 Brain Friendly Habits and How to Lead with the Brain at Work. Plus a range of tools to help yourself and others including questionnaires, values cards, posters and more.