For those of you who have dogs or are dog lovers, you’ll understand the appeal of the local dog park. For me, it is my happy place, and for my Labradoodle it is a dive into scent heaven.

It can also be fascinating to watch how the dogs instinctively seem to know exactly which dog will welcome them going up for a sniff, while they tend to stay well clear of others for no obvious apparent reason.

Our brains are primed to reduce threat, and even us humans will be scoping our work environment, picking up signals and vibes about who to approach today and who not. In fact our brains default to ‘foe’ rather than ‘friend’ despite our natural inclination to be connected to others. This is the challenge we have with the human brain – we are also affected on a social level, not just on a physical level like our four legged friends.

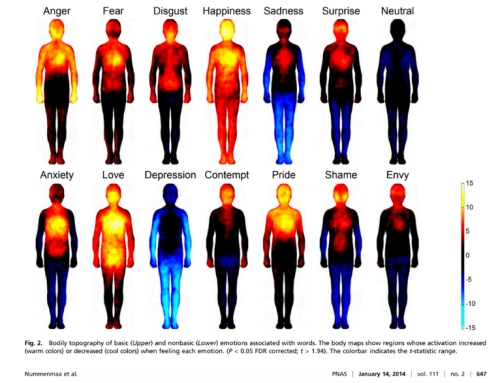

Social neuroscience explores the biological foundations of the way humans relate to each other. This field has found that much of our motivation driving social behaviour is governed by an overarching organising principle of minimising threat and maximising reward (Gordon, 2000). It has also found that several domains of social experience draw upon the same brain networks to maximise reward and minimise threat as the brain networks used for primary survival needs (Lieberman and Eisenberger, 2008).

What this means for leaders in the workplace is that despite their good intentions, our environment can sometimes default into being a fear-based one. It is essential to make a concerted effort to avoid this to minimise threat responses, and you can start by understanding what may trigger fear and what it does to us.

In the workplace, fear can be very insidious. It shuts down our thinking and leaves no space for clarity. We end up getting foggy brains and are unable to regulate our emotions. When experiencing fear, no matter how subtle, we are being driven by emotions that are all about protecting us, so we effectively cut ourselves off. It’s almost as if your employees will be going about their typical day yet with an invisible wall built around them, and that wall prevents any genuine exchange.

David Rock’s SCARF model is an excellent tool for leaders to really understand what can trigger threat responses, and on the flip side, reward responses. Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness and Fairness are the five domains that yet help leaders understand workplace interactions and maximise engagement and motivation. Relatedness is the domain that shines a light on the social science side – humans have an innate need to belong, and when leaders can create the sense of belonging within their teams, they will trigger the reward response.

By understanding the importance of social neuroscience in the workplace, leaders can create high trust cultures that will deliver measurable improvements in team communication, collaboration and performance.

Deb is a Senior Consultant who is passionate about Positive Leadership and brings with her a wealth of experience in applying Positive Psychology and the Neuroscience of Leadership to excel in leadership and performance. Book here for a conversation to learn more about our leadership and capability programmes.