Do you want to make savings and improvements in your business? Start by asking the right questions.

Asking good questions is an art that business leaders, owners and entrepreneurs sometimes forget as they strive to improve the bottom line. In the quest for ever greater efficiencies, productivity and general cost saving, a few key questions can reveal hidden costs and open up new avenues to increase performance and profitability.

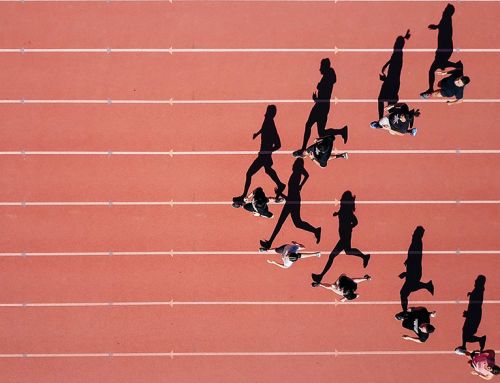

How can we learn from our best performers?

An over-attachment to a view of organisations as a set of roles and role behaviours, with expected minimum standards of performance can blind us to the exceptional performance of our best staff. Focused on trying to prevent our worst performers from costing us money, we don’t always focus on really examining how our best performers make or save us money. Research into these examples of positive deviance has demonstrated that there are distinctions between the best and the rest; and that these distinctions can frequently be small and replicable by others.

For example Atul Gawande, a general surgeon, was interested to learn more about how an increase in life expectation for people with cystic fibrous had been achieved. The first hospital he visited had a good track record and an array of processes and procedures for treating and supporting those with CF. He was impressed. Then he visited the top performing hospital where the life expectation of people with CF under its care is almost double the average. What he found was while they too provided excellent care in all areas, they had one key feature, lung capacity, that made the critical difference to positive outcomes. It was the single-minded care and effort that went into supporting people to maintain or improve their lung capacity that seemed to be the distinguishing feature. This is not something he could have learnt by studying the worst, average or good-enough performing hospitals.

Someone in your organisation demonstrating double the sales figures, or twice the academic success rate? Be curious. Study and learn.

How much is this saving costing us?

When people or organisations focus in on areas where savings might lie, and start to implement processes to realise those savings, they don’t always account for the hidden costs of administering the process or achieving compliance.

For example insisting that all requests for facility repairs are submitted to be assessed and approved by a manager might seem a good cost control idea. However as some Housing Associations have realised, the hidden costs of bureaucracy and close scrutiny can be greater than the cost of many minor repairs. If the bureaucratic delay means that the situation then escalates into a formal complaint or dispute then costs rise more and senior manager time starts to be eaten into.

Some housing organisations have started to give front line staff direct access to budget to authorise payment for repairs. Not only has the overall repair budget not risen, the benefits of engaged and committed staff who feel they can really make a timely difference and be helpful, and more satisfied clients, have been a real bonus to organisational culture and reputation.

In the same vein I recently read that the administration of the competitive tendering process in the UK National Health Service (NHS), that is the bureaucratic, managerial and legal costs, are conservatively estimated at £10 billion every year (and that’s not counting the time spent by those hopeful of securing a contract submitting exhaustive tender applications for relatively small contracts). So we know how much is the ‘saving’ is costing the NHS, do we know how much it is saving in real terms?

What behaviour do we want and what behaviour are we rewarding?

Over time perverse incentives creep into organisational life. As people make changes, launch initiatives or develop projects misalignments can occur between the desired behaviour and the behaviour rewarded by the contingences of the system.

An example I have come across often concerns sales people. Rewarding sales people on their individual sales is a time-honoured motivational system for many sales staff. However, it is not uncommon for an organisation to realise at some point that they are missing out on opportunities for cross-selling, either across products or between areas. They introduce a load of cross-product training and encourage people to try to sell other products, or introduce their colleagues to their clients. If the reward system hasn’t changed, to spend time doing this is perverse since it lessens the time available for selling more of the thing you do get rewarded for. So there is a hidden incentive in the system not to spend time cross-selling which reduces the value that could be achieved.

How can we help people spend more time doing things they enjoy and less time doing things they don’t?

It is not always apparent to people the high cost of trying to get people to do things for which they have no aptitude, and less liking. Firstly, when people have little aptitude for a part of their role the return on investment of trying to train them to do it can be invisible. In other words hours of management time might be devoted to improving skills in this area to little avail. Secondly, even the most conscientious of people will be drawn towards putting off those parts of their job they dread, while the less driven find endless ways not to be in a position to do the hated deed. Somehow we get focused on the short-term objective, getting this person to acheive it, and lose sight of the bigger picture, which is just that a particular outcome needs to be achieved; not necessarily in this way, not necessarily by this person. In other words, sometimes we would be better off to step back and ask “Who would be better suited to this task?” or “How else can we achieve this objective?”

On the other hand, we know that people using their natural strengths, all other things being equal, are usually highly motivated, engaged and productive. Doing what we feel good doing is motivating, while struggling with things about which we feel a hopeless inadequacy and dread (not the same as the nervousness we feel at the start of an eagerly anticipated learning curve) is demotivating. Demotivated people are a cost to your business.

How can we make our workplace a great place to be?

To some extent sickness absence is a discretionary behaviour. Clearly at one extreme we are too ill to rise from the bed, while at the other we are bursting with health and vitality. Between these extremes is the grey zone: tired, hung-over, a bit down, cold coming on, a bit head-achy, it could be flu etc. Two factors affect whether that person decides to go into work or take a day off. The push or pull factors of the alternatives: for example, the pull of a sunny day or the push when their mates are away and they’ve no money to spend; and, the push and pull factors of work. Push factors at work might include being fed up with the tasks they’ve got at the moment, problems with colleagues or feelings about their managers. Pull factors include loving the work, enjoying the company, feeling appreciated on a daily basis, believing their presence makes a real difference and feelings of mutuality and loyalty. Obviously you don’t want anyone coming in when they shouldn’t and spreading infectious diseases, but beyond that a great place to work is likely to have a positive effect on attendance rates.

Appreciative Inquiry is the art of asking the right questions to reveal new insights and shape a positive future.

[This article was first published on Sarah’s website, Appreciating Change.]

Click here to learn more about the Langley Group’s Positive HR Toolkit. The Positive HR Toolkit gives leaders and HR professionals the solutions to implementing positive people practices in the workplace. Built on research from Positive Psychology and neuroscience, the solutions provide simple and easy to use tools for every stage of the employee lifecycle.